⊕ LIBRARY | SOCIETY. |. 03.SEP.2018

What Is Wrong with Modern Times

_

The conditions of modernity are in many ways profoundly better than those under which the vast majority of humanity lived for more or less the whole of history. But, along with its manifest benefits, modernity has brought a special range of troubles into our lives which we would be wise to unpick and to understand. |

|

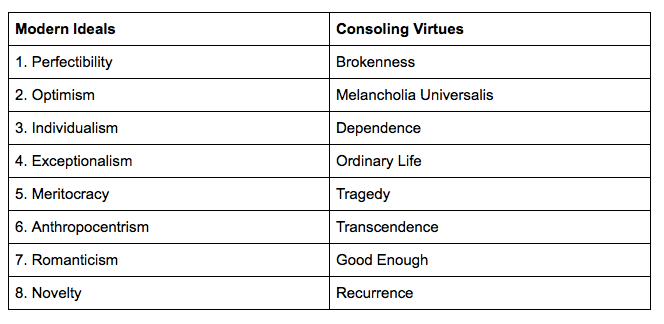

Part I: The Ills of Modernity The conditions of modernity are in many ways profoundly better than those under which the vast majority of humanity lived for more or less the whole of history. But, along with its manifest benefits, modernity has brought a special range of troubles into our lives which we would be wise to try to unpick and to understand. Without as yet pushing in detail for what the solutions might be, we identify eight central ills stemming from certain of modernity’s leading ideas: 1. Perfectibility A fundamental tenet of modern societies is that perfection is within our grasp. Science, that most prized of contemporary tools, seems to guarantee us that we will, eventually, be able to overcome all that bedevils us, the pain, stupidity and error which make us so much less than we might be. It is simply a matter of time. Our societies stress that it is within our capacities – individually and collectively – to aim for perfection. The modern era was founded upon the experience of astonishing improvements across almost every field of endeavour: we learnt to heat our houses, to feed and clothe ourselves adequately, to criss-cross the globe, to defeat disease and to introduce reliable mechanisms for learning, law and justice. Our many improvements have imbued us with an unparalleled confidence, resulting in a notion that progress should be deemed a preordained and general rule of existence. We know that we may of course, right now, be facing considerable challenges and reversals and that there is much evidence of our ongoing proclivity for stubbornness and stupidity. But we refuse to hold our sorrows as inevitable: they are, rather, a sign of interrupted and delayed progress. Even death may one day be solved. A problematic result of this grand vision of human progress is that our ongoing imperfections weigh upon us all the more heavily: we are prone, more than our forebears, to feel profoundly frustrated, impatient, cursed and betrayed with all that continues to defy our will. We respond to political or economic stagnation with rage at the stupidity of those who lead us; we are unwilling to countenance (as our ancestors once did) that human societies are hugely complex machines. The unhappiness of relationships is quickly ascribed to being with the wrong person – as opposed to the result of the inherently arduous goal of trying to be happy in multiple dimensions with another person over a lifetime. We are no less ambitious around our labour. We look askance at the previous, routine assumption that our jobs would always, in some ways, be something of a curse: we no longer work merely for money, we work to fulfill our souls. As for our psyches, we believe ourselves capable of overcoming any confusion or compulsions generated in our childhoods and of mastering our minds through the insights of therapy. For most of history, we lived with a degree of reconciliation to the idea of ongoing woe and turmoil. With modernity was born the beautiful and fateful notion that this world could through the application of intelligence be rendered conclusively saner, more manageable and kinder. The origins of this attitude were immensely noble but the results have been strange and unexpected. We have too often come to despise and lament the actual conditions of our lives. 2. Optimism Modern societies are profoundly optimistic in temper. They imply that our manner should be upbeat, our spirits high and our greetings enthusiastic. Expecting things to go well is presented as the best way to ensure that they will in fact do so. And presenting a cheerful front to others is assumed to be a reliable method for getting them to like us and to build up sincere bonds with strangers. But our optimism has been a curse. When sunny expectations meet with an obstacle, they are readier to flip to its opposite, anger. Betrayed hope places us at greater risk of nit-picking, sulking, irritation and rage. What these behaviours have in common is insulted optimism: they are the legacy of a feeling that things were meant to be so much better than they have turned out. We are shocked and offended by the stupidity of others, the failings of institutions, the greed and selfishness that circulate and the prevalence of what feel like unwarranted errors. We are outraged by the immemorial condition of the world, our lives consumed by a disappointment fermented by what began as the sweetest of outlooks. These dangers aside, we are pushed to imagine that being optimistic will make us more attractive to others; but oddly a determinedly jolly and upbeat outlook can in fact cut us off from communion with those around us, for our most profound reality is that we all have deep zones of worry, regret, inadequacy and shame that we long to see reflected in others and cannot when the mood must be sunny. It is the confession of darkness that allows us to get genuinely close to another person – just as it is insistent optimism that will, unexpectedly, reinforce us in our loneliness. 3. Individualism For most of history, all that was felt to be required to understand a person’s identity were a set of facts that had pretty been much settled at the moment of birth: one was defined by one’s gender, by the social rank of one’s parents, by the geographical zone one was born into and by the religious sect one’s family belonged to. But in the second half of the 18th century, a new ideology began that set its face against all accidents of birth and beckoned us to fashion ourselves in our own style across our lives, a hopeful, dynamic philosophy known today as individualism. When we meet a stranger, we do not, as in the past, ask them about their ancestors, their religion, or the place they grew up in. We ask them, first and foremost, what they ‘do’, for it is our work that has, more than anything else, come to be seen as the crucible of our individuality. However, the connection between work and selfhood has ushered in distinctive new problems, for a work-based identity is by its nature extremely unstable: we are a sacking, a profit downgrade or a retirement away from losing an established sense of self. Equally, we may be transformed by a promotion, a newspaper profile or a flotation. Our identities are caught in a turbulent oscillation between hope and fear. Our job-oriented identity is further buffeted by the constant presence of competition in a market economy: our status depends on victories over others. We can become impressive only if others fail. And if they succeed, our own attainments lose their lustre. We end up wanting others to sink because, every time they do so, our own prestige will be enhanced. Without any intentional malice, we have constructed a world of continuous psychological as well as economic rivalry. An individualistic philosophy centred on careers means that what we do outside of paid work comes to seem negligible or irrelevant. Our efforts with our families, our friendships, our enthusiasms don’t count in the eyes of others as any real answer to the question of ‘what we do’ because these pursuits are disconnected from a salary – and so must in turn grow diminished in our own eyes. There is a harsh irony: individualism was supposed to highlight our unique, intimate character, but it has in practice sharply reduced our sense of who we might be. It is not surprising that the first great sociologist to investigate suicide – Emile Durkheim – discovered that the more individualistic a society becomes, the more the rate of suicide rises. It is not poverty or illness as such that drive us to the ultimate act of despair. It is the sense that who we are has no meaning outside of visible success in the realm of work. 4. Exceptionalism Modern societies continually stress that it is within our powers to achieve a mighty destiny. Whatever the initial hurdles, we can, so the suggestion goes, overcome them all through hard work and the exercise of the will – and thereby forge an exemplary and extraordinary path. We may reach other planets, amass fortunes, run the country, make stunning discoveries in science or produce an outstanding film or novel. We do not have to adhere, forever, to that most dispiriting of epithets: ordinary. We can, through our effort and brilliance, escape the herd. This emphasis on heroism is meant to be encouraging. We are asked to feel that we too could – whatever obstacles we face – astound the world. This belief in the potential of all has a deeply generous origin, but its effect is profoundly punitive, because we are inevitably destined to be very ordinary in most aspects of our lives. By necessity almost all of us will aggregate around the average, an unheroic truth emphasised by a central image of statistical analysis, the bell-curve. Most of us will have close to average incomes, close to average relationships, more or less average looks and deeply average talents. In any aspect of life, in any quality or endeavor, only a fraction of the population can ever stand out. But even though we are destined to be ordinary, we live in a culture that ardently neglects or disparages this basic truth. It emphasises the likelihood of satisfying marriages, though 95% of unions are merely tolerable compromises; it speaks of great jobs, though 95% of employment will be significantly compromised; it valorises fame though there are hardly any famous people (let alone contented famous ones). Our sights are set on deeply improbable objectives. It feels cruel to rule them out, but it may in reality be even crueler to incite them. As a result of a generously intended idea, we end up despising the actual conditions of our lives, hate ourselves for not having done more, bitterly envy those who have triumphed and neglect to appreciate the qualities of what and who is actually to hand. 5. Meritocracy Our societies firmly believe in the concept of meritocracy, that is, the faith that we should be free to make a success of our lives if we have sufficient talent and energy and that there should be no obstacles to our efforts based on class, gender or race. All voices on the political spectrum are committed to an ideology which states that the highest form of political justice is a nation where the talented can rise whatever their backgrounds. A good society has become synonymous with a meritocratic one. However, this very well-meaning idea carries with it some rather less appealing implications, for if we are to believe that those at the top truly deserve their success, then those at the bottom must surely truly deserve their failure. Under the aegis of a meritocratic worldview, an element of justice enters into the distribution of penalties as well as rewards. We move from thinking of the poor as ‘unfortunates’ – deserving of compassion and kindness – to thinking of them as something far harsher: ‘losers’. A society that thinks of itself as meritocratic converts poverty from a condition of honourable, if painful, bad-luck into evidence of personal incompetence. The burden of failure rises exponentially. 6. Anthropocentrism The modern age is inherently anthropocentric in outlook (fromanthropos, Greek for human), that is, it places human beings and their experience and concerns at the centre of the hierarchy, above the claims of nature, animals, gods or the universe more broadly. We are now, in every way, in our own eyes, at the centre of the show. It was not always thus. Religions traditionally declined to give human beings a pivotal or anointed place in the cosmos. The ancient Greeks pictured their Gods living on the summit of Mount Olympus and looking down upon humans with a mixture of amusement and pity. Zen Buddhism interpreted nature in general, with all its diverse flora and fauna, as far more important than any single creature, even one that mastered fire and language. And Judaism and Christianity presented the world ‘theocentrically’, with human life as a small, not very impressive fragment in a much larger scheme known only to the infinitely superior mind of God. Our attention would, in the historic past, constantly have been drawn back to theocentric or biocentric perspectives. In ancient times, in the Parthenon, on the Acropolis above Athens, there stood a ten-metre tall statue of Athena made of gold and ivory. No merchant, statesman or general, however accomplished in human terms, could look upon it and think of themselves as anything other than insignificant. In London, after the huge fire of 1666, the largest part of the city’s revenue was assigned for decades to the building of St. Paul’s Cathedral: an edifice massively larger and more impressive than any other of the time. The Cathedral radiated across the city the fundamental idea that life on earth would be fleeting, our concerns slight and our personal triumphs petty in comparison to the glory of an omnipotent, omniscient and eternal God. With the decline of religion we have come to embrace a philosophy of what we can term anthropocentrism: we have identified ourselves, as humans, as the most important things that exist. It’s a move that can be cast as a liberation. The stories on which God-focused societies were founded have been displaced by tales of human heroism in business, science or the arts, but this liberation has brought an unexpected kind of suffering in its wake: a vicious sense of our own lack of importance as compared with that of certain esteemed others. It has unleashed a torrent of envy and inadequacy. Theocentric or biocentric societies cast all our eyes upwards or sideways and attenuated destructive internecine feelings by reminding us that we were, everyone of us, in the wider scheme, ultimately, puny and forgettable propositions. But, in our times, there is now no established point of reference beyond us that can matter. What happens to us here and now is framed as overwhelmingly important; it is all there is. And so everything that goes wrong, everything that frustrates or disappoints us fills the horizon. The idea of something bigger, older, mightier, wiser and nobler than us to which we owe love and obedience has been stripped of its power to console us. Religion, for its part, located the important events at distant points in time: in the age of myths and heroes or in the year 33 AD when Jesus was crucified. The events of our own days would be seen as mere ripples and minor accidents in the immense fabric of theological time. There was nothing very special about now. Our natural instincts to panic and despair were reduced by being set within the grandest of perspectives. The theocentric view of religion made it impressively clear that the so-called great figures in society were not really so great. They might indeed have power over us, but they in turn were nothing as compared to divine authorities. The Greeks built into their culture stories, which they told themselves again and again in poems and plays, of how their greatest king, Agamemnon, was gruesomely punished by divine justice for the arrogance of his life. He was above all other people, but he was still a lowly subject of the Gods. The story was still being retold in the 18th century, when the German composer Gluck set the central words to music: ‘great kings to whom all must bow, must themselves kneel before the Gods.’ A non-anthropocentric outlook allowed us to perceive ourselves as beautifully unimportant and rather ridiculous. How long we might live, whether we were very successful or not, how intelligent we were or how beautiful, would be absurd concerns from the point of view of a deity, Mount Olympus or the distant planets. We were invited, usefully, to see how unimpressive our merits all ultimately were. In modernity, we have been left without these comforts and reliefs, tormented by a stupefyingly heavy sense of our own importance in a nevertheless wholly indifferent, random and unequal universe. 7. Romanticism The modern era has been powerfully shaped by the notion that romantic love lies close to the meaning of life. The point of relationships is no longer just to help to rear children, pass assets down the generations or assure a tolerable friendship between two people: their point is to assure superlative contentment and spiritual and physical communion. Sexual relationships are not one kind of connection among others, they are – the ideology of Romanticism assures us – the only kind of connection worth valuing. From the end of the 18th century onwards, there emerged, in the minds of poets and artists, a view of life which privileged sexual monagomous lifelong love over all other values. Angels, who had previously been believed to dwell in heaven, were relocated on earth and took up human form. We could all, with a little luck, find redemption through the love of a fellow member of our species. With hugely good intentions, Romanticism encouraged us to place an impossible burden of expectation upon a partner. We would ask them to be our lover, our best friend, our confidant, our nurse, our financial advisor, our chauffeur, our co-educator, our social partner and our sex mate. And then, when they failed in a few of these roles, as they inevitably would, we were to interpret their inevitable imperfections as a sign, not that we had got to know someone properly, but that we had mistakenly come together with the wrong person. Romanticism projected a set of beautiful ideas onto relationships. But the consequence of this ideology has been the discovery of extensive new ways of feeling dissatisfied, disappointed and ashamed around ourselves and our partners. It has made us a good deal more lonely – and notably less able to love. 8. Novelty Modern societies assign immense prestige to whatever happens to be new. ‘Progress’ and ‘innovation’ are central terms of praise; to be ‘old-fashioned’ or ‘out of date’ is little short of a disaster. One manifestation of this attitude is that we instinctively prefer youth to age. The ideal age is located roughly between nineteen and twenty-five, this is the cohort assumed to be at the heart of change: these are the people who have new ideas, new outlooks, new kinds of music and the right sort of spirit. Getting older is automatically to move away from novelty and hence goodness; we set ourselves up for decades of lamentation. This contrasts radically with the outlook of traditional societies in which the young were admired only to the extent that they held out a promise of eventually becoming wise ‘elders’. Our modern devotion to novelty shows up additionally in our preoccupation with ‘news’. News is our name for the information we think of as most important which is taken to be synonymous with what has happened in the last twenty-four hours – or the last five minutes. We conflate the recent with the significant. But, of course, this focus on the present cannot do justice to our needs, for the information we truly require might be located at more distant points in time. In order to live and die well, we might need to encounter ‘news’ from Socrates or Lorenzo de Medici, Schopenhauer or Jane Austen, but since these people have done nothing for decades or centuries, we’re very unlikely ever to hear about them in our headlines. Modernity’s love of novelty is intended to grip our attention and bring excitement and connection into our lives; but by a strange twist of fate it has left us – often – feeling superficial, fragmented, hollow and distracted. This has not been a list of all that is wrong with the modern world; there are many additional political, economic, legal, administrative and cultural defects that could be mentioned. What’s distinctive about the troubles we have discussed is that they are philosophical and psychological in nature: they concern our intimate sense of who we are and what our lives are about. The task is to try to repurpose certain ideas – many from our religious pasts to help guide us – and soothe our agitated and confused psyches. Part II. Consolations To counter the ills of modernity, we propose eight leading ideas: 1. Brokenness Although a generous and visionary idea, our belief in human perfectibility has driven us to collective disappointment and rage; we stand tormented by the notion that our problems could, with sufficient intelligence and effort, be rendered avoidable. Our belief in perfectibility is very recent and strange in historical terms. For thousands of years, the inherent brokenness of the human animal was a cultural given. All substantial human endeavours – marriage, child-rearing, a career, politics – were understood to unfold against a backdrop of fundamental blunder, and were accepted as sources of distinctive and elaborate misery. Buddhism described life itself as a vale of suffering; the Greeks insisted on the tragic structure of every human project; Christianity characterized each of us as marked at birth by a divine curse. Such gloomy outlooks feel – at first – as if they could only guarantee further misery. But, in reality, they have the reverse effect. A philosophy of brokenness makes the many sorrows we will inevitably be subject to feel normal and hence more bearable; and casts any better eventuality as unlikely and, therefore, as something for which we can be intensely grateful. In the late 4th century, as the immense Roman Empire was collapsing, the leading philosopher of the age, St Augustine, became deeply interested in possible explanations for the tragic disorder of the human world. One central idea he developed was what he legendarily termedPeccatum Originale: original sin. Augustine proposed that human nature is inherently damaged and tainted because – in the Garden of Eden – the mother of all people, Eve, sinned against God by eating an apple from the Tree of Knowledge. Her guilt was then passed down to her descendants and now all earthly human endeavours are bound to fail because they are the work of a corrupt and faulty human spirit. This odd idea might not be literally true, of course. However, as a metaphor for why the world is in a mess, it has a beguiling poetic truth, as relevant to atheists as believers. We should not – perhaps – expect too much from the human race, Augustine implies. We’ve been somewhat doomed from the outset. And that can, in certain moods, be a highly redemptive thought. It is not hard to recast the concept of original sin in contemporary terms. It is not our souls that are broken but, as neuroscience teaches us, it is our minds. These minds, the faulty walnuts we interpret reality through, did not evolve in ways that render them easy companions in the harried conditions of modern life. Our emotions kick in powerfully before we’ve understood situations and swamp our fragile powers of reason; our appetites (for example, for sugar and sexual stimulation) are strong and insistent – and fatally attract us to things that no longer serve our best interests. Our childhoods bequeath to us all sorts of distortions which marr our ability to understand ourselves, communicate adequately and trust others. We emerge into adulthood with an extraordinary quota of debilitating quirks, blinds spots, unhelpful obsessions, stark limitations, exaggerated worries, structural character flaws and distorted reasoning processes. And it’s not just we who are broken: the same logic applies universally. We live in societies entirely made up of broken souls. Our intelligence may give us a theoretical chance to straighten out our lives and some of our machines are properly astonishing, but stupidity is too deeply entrenched ever to be eradicated conclusively. Science will never be quite the answer we assume it will be. Our technology has a devilish habit of serving, rather than abetting, our folly. The dream of modernity was that stupidity would be eradicated by science and learning; instead, it seems that our intellectual capacities are fated to coexist alongside, and be inflamed by, our moral and psychological flaws. We remain barely evolved aggressive apes, in command of nuclear weapons. With these dark facts in view, we should orient ourselves calmly towards ideas that will help us cope with our unavoidably broken natures. Self-acceptance bids us to accept without undue self-contempt or misery that we will – on a regular basis – commit gross errors, hurt those we care for, fail to seize opportunities and make irrational choices. We are not uniquely cursed, merely members of a predictably flawed race. Aware of our proclivity to error, we should more graciously forgive those around us when they slip up. They (like us) were not evil so much as tired, over-wrought, frightened and out of control; human, all too human. We should mobilise the idea of brokenness for the sake of generous, imaginative explanations of the less than ideal behaviour of others. An instinct for vengeance and moralism can give way to a keener readiness for patience and pity. 2. Melancholia Universalis A form of jolly optimism might sound like an ideal state of mind, but it has very little in common with what is truly required for a well-lived life. We would be advised to trust instead in a philosophy of universal melancholy, melancholia universalis. A panoply of genuinely sad things will occur in every existence, pretty much every day. Fundamental sources of sorrow are everywhere: everything we love is vulnerable while most of what we are pained by is solidly established and resilient. We are condemned to have to leave the world with much of our business unfinished and many hopes unexploited. We won’t have achieved even a small fraction of what at some points felt possible; we’ll have missed an endless array of possibilities; we’ll not have put our relationships into proper order, we will have countless reasons to be bathed in regret. At the same time, there was no alternative. We are required to make decisions far in advance of experience or reliable data: we are steering blind. We had to decide on a career before we truly knew what a career might might mean; we had to commit to another before we genuinely knew what a joint life would entail. A war could have been avoided; an election could have gone a different way; an accident might not have happened; a cancer cell could have been benign; we might have fallen in with a different group of people when we were twenty-one; we might have had a more understanding boss; we could by chance have struck up a conversation with a wonderful stranger. We live in a universe of unknown options, of divergent futures and unexamined possibilities. We each have a private version of these woes, but they are individual variations on what is ultimately a universal theme: the metaphysical sorrows of life. They arise because of life, not because of us. Whatever we do, whatever our situation, they will afflict us. No one escapes. Non-optimistic cultures and religions have made the point central to their ideologies: ‘life is suffering’ in the Buddha’s famous summation. To never have been born may be the greatest gift of all, said the Greek tragic playwright Sophocles; Christianity habitually described the world as a vale of tears. These profoundly sad summations were not intended to depress us. On the contrary a universal sense of melancholy was envisaged as a valid, redemptive element in a properly lived life. The wisdom of the melancholy attitude (as opposed to the bitter or angry one) lies in the understanding that we have not been singled out, that our suffering belongs to humanity in general. Melancholy is marked by an impersonal take on suffering. It is filled with pity for the human condition. We need a public culture that remembers how much of life deserves to have solemn and mournful moments and that isn’t tempted – normally in the name of selling us things – aggressively to deny the legitimate place of grief. Melancholy is not rage or bitterness, it is a noble species of sadness that arises when we are open to the fact that life is inherently difficult for everyone and that suffering and disappointment are at the heart of human experience. It is not a disorder that needs to be cured; it is a tender-hearted, calm, dispassionate acknowledgement of how much pain we must inevitably all travel through. Melancholy isn’t directly opposed to cheerfulness. If we accept that life is sad and difficult, we don’t always have to stay tethered to this fact. We can open ourselves to the possibility of what might be called ‘cheerful despair’. Despair can be the standard, tragic, expected background against which anything sweet, amusing and tender stands out and can be properly appreciated. Once again the ancient Greeks provided a useful model for thinking about this. They liked to contrast the attitudes to two philosophers: Democritus and Heraclitus. When they looked at the world Heraclitus was moved to tears, Democritus found himself laughing. Democritus laughed not out of naivety or indifference or cruelty but because he had already factored in a deeply sober and realistic account of all that is wrong with the world. He wasn’t shocked that people are selfish, that we turn to violence when thwarted, that we make endless errors, that we are swayed by our appetites more than by our reason, that we betray one another, that we are sly and deceitful – all this was obvious to him. He laughed because he knew it all already – and had in the meantime spotted a few beautiful things to be content about and charmed by. Ironically, gratitude becomes all the more powerful when we don’t take the good in any way for granted. Armed with a philosophy ofmelancholia universalis, we can be genuinely delighted when someone is considerate or generous, patient or kind; we’re thrilled when things happen for once to go well; the happiness of a dog chasing a stick can move us, because we know how rare unbounded joy is; many little sources of pleasure become dear to us because we grasp that they buck the trend of universal sorrow. We’re less obsessed by what is missing from our lives and more grateful for the limited but really good things we do possess. And so, ‘little things’ start to seem somewhat different; no longer a petty distraction from a mighty destiny, no longer an insult to ambition, but a genuine pleasure amidst a litany of troubles, an invitation to bracket anxieties and keep self-criticism at bay, a small resting place for hope in a sea of disappointment. We appreciate the friendly encounter, the long hot bath, the spring morning – and keep in mind how much worse it could always, and probably will one day, be. 3. Dependence Individualism has made us sick; our consolation lies in a culture that properly respects the notion of dependence. A philosophy of dependence acknowledges that we are not capable of achieving more than a fraction of what matters by ourselves. Our sense of who we are should therefore be focused not so much on our unique possessions and accomplishments but upon the many good things which have come to us largely through the efforts of others. A striking incidental example of this attitude can be found in ancient Athens. In the 5th century BC, under the leadership of Pericles, the Athenians developed the idea that the public parts of their city should significantly surpass any private dwelling in terms of beauty and grandeur. They repudiated an attitude that would later be termed by the Roman historian Sallust publice egestas, privatim opulentia – public squalor and private opulence. They wanted public opulence and were willing to forgive private modesty. A home might be a simple wooden affair but the temple one visited twice a week would be majestically carved of limestone; the shopping area would be graceful; the theatres and gymnasiums would be places of charm and elegance. One’s sense of pride wouldn’t – therefore – focus merely on what one had privately amassed but on how fine collective possessions happened to be. Self-esteem wouldn’t depend on whether one had a nice dining room; it would matter so much more that a superb statue had been erected in the public square or that a new portico – where anyone could go to listen to Socrates and the sophists debating – had been built with unusually graceful ionic columns. The contrast with our own times is painful. We find it almost impossible to imagine that a shopping centre might genuinely be more beautiful than a home or that new law courts could be visually more delightful than an upmarket beach resort – and hence that we could, with reason, be proud of the achievements of our society and not merely of our own private selves. The Athenian view of public architecture is a specific point at which we meet the idea of dependence, with its belief that our sense of identity can legitimately be shored up by collective acts in which we may not have played any outstanding role. But, more intimately understood, the same idea of dependence arises as we recognise how much we owe our own development to the care and tenderness of others. Who we are is only very partially the result of our own toil. It has to do with the labour and continuous concern of parents, guardians and the collective more broadly. We can’t be understood – and can’t understand ourselves – as self-created monads or independent apparitions. We are always, to a vast extent, the undeserving recipients of the help of others and are the better for recognising the fact with modesty. It’s a dependence that should be admitted with gratitude rather than buried in shame. The mummy’s boy or girl may be criticised in a highly individualistic society, but they capture a sensitive and profound truth: that we all have an ongoing need for comfort and reassurance, whatever age we happen to be. None of us can quite survive alone. In order to flourish, we can’t look simply to our own unique strengths, we need to allow ourselves to be helped by, and therefore to become dependent upon, the intelligence and talents of others. However accomplished we are, there will be areas of inevitable inadequacy: we may be sweet natured, but not very strategic; we may be creative but a poor marketer of our own creations; we may be highly imaginative but lack the poise to make good decisions. In a more collective, dependent vision of identity, a focus of pride emerges in the contribution we can make to the public, rather than individual, good. Our role may be quite small and yet entirely real. In the Middle Ages, when Chartres Cathedral was being built, more or less the entirely local population had a hand in the work. They might only be pushing a cart, carrying stone from the quarry, or they might be carving a tiny flower high up on a wall; they might be making lunch for the master masons or cutting timber for the scaffolding – but each was doing something that ultimately mattered for an immense final result. Their identity didn’t focus simply on what ‘I’ did but on what ‘we’ could do together. Chartres Cathedral: a sense of identity rooted in communal dependence It feels odd, for many people, to feel local or national pride. Being proud of one’s city – which would have seemed obvious to a sophisticated ancient Greek – feels shameful and absurd to the educated modern imagination; loving one’s country and being grateful to it gets recast as undignified, sinister nationalism. But, when we admit dependence into our picture of ourselves, we take attention away from our own individual merits. We’re not asking others to admire us solely for what we, personally, have done. We didn’t make our city or our country, we didn’t establish the company, we didn’t bring ourselves up, we didn’t teach ourselves to read and to think. A degree of modesty emerges. Our sense of who we are – our identity – becomes more expansive, more secure and less rooted in individual feats. And the buffetings of personal inadequacy count for proportionally less in the story of who we are. We can be full, valid people even if our own feats are limited and our powers circumscribed, because we’re no longer forced to base our dignity on an impossibly narrow premise. Unfortunately, it is nowadays not easy for us to find compelling counters to the logic of individualism. For multiple reasons the prestige of broad, dependent kinds of identity has been removed. We cannot feel good about ourselves by being members of a church (because it asks us to believe incredible things); we cannot pride ourselves on our families (because it seems parochial); we cannot define ourselves by our nation (because it feels chauvinistic); we cannot take pride in being, like the quarry workers at Chartres Cathedral, small cogs in a vast enterprise (because our corporations and institutions don’t feel noble enough to warrant devotion). We are thrown back on ourselves – but at the same time, conscious of our underlying frailty, await the rediscovery of a plausible philosophy of dependence. 4. Ordinary Life Modernity emphasises the glory of heroic achievement. It prizes excellence and disparages the norm. And it does so through the medium of art, understood in the widest sense; in adverts, films, magazines and novels, we are shown – often with great verve and skill – what is supremely impressive, appealing, intriguing and delightful about the lives of unusually successful people. The contrast with our own lives, could not be greater or more humiliating. But it is not the case that ordinary life is devoid of virtue, simply that we do not generally muster creativity and aesthetic energy to discover it. The consolation for our sense of comparative failure would be to look more accurately – with more sensitivity and more artistry – at the real beauty and sweetness of some of what surrounds us. At various points in cultural history, important initiatives have been made in this direction. In the 1650s, the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer painted a series of works in which he sought to show us what could be appealing and honourable about very ordinary activities: keeping a house tidy, sweeping the yard, babysitting, sewing or preparing lunch. The woman featured in his Milkmaid has perhaps not had a moment to herself since she woke up; over the years she’s only been able to accumulate a tiny nest egg; she’s not her own boss; she’s not especially proud of her looks. But to Vermeer she’s a full and lovely individual. The painter was doing for her – and by extension for us – what, up to then had mainly been done for generals, princes and popes: framing for a moment and forever the genuine beauty and dignity of a unique being. In another picture, Vermeer studied what might be appealing about living in a modest house in an unfashionable area of Delft. The paint is peeling from the window frames, no gilded carriage is ever going to roll up at door; they have to keep a close eye on the budget. But good lives unfold here nevertheless. Vermeer was insisting that ordinary life is heroic in its own way because ordinary-sounding things are very far from easy to manage. There is immense skill and true nobility involved in bringing up a child to be reasonably independent and balanced; maintaining a good-enough relationship with a partner over many years despite areas of extreme difficulty; keeping a home in reasonable order; getting an early night; doing a not-very-exciting or well-paid job responsibly and cheerfully; listening properly to another person and, in general, not succumbing to madness or rage at the paradox and compromises involved in being alive. Our misfortune is that the efforts of artists like Vermeer have been relatively unusual; the general tendency has been to make us experts in understanding the allure of the lives of the very few, while overlooking and underestimating the very real beauty, honour and appeal of the lives we are already living. The process is endlessly repeated: the best novelists make us see what could be lovely about lives entirely unlike our own: being a spy or a 19th-century aristocratic adventurer, a wizard or a rebel general in a war in 2302. The real feat would be to take a life very much like ours, with its particular limitations, frustrations and enthusiasms and render it in parts desirable (which, in truth, it probably is). The pleasures of our lives may look very minor – waking up early in summer, whispering in bed in the dark, talking to a grandparent, scanning through old photos – and yet be anything but. If properly grasped and elaborated upon, these sort of activities may be among the most moving and satisfying we, or anyone, can have. It’s just that a warm bath, an apple, a conversation with a close friend or a good night of sleep – lack prestige or social support. We don’t feel we’re living theright life, though we may, in fact, be living a good life. The ordinary would, ideally, stop being a category of shame. We would fully and properly recognise how ‘the ordinary’ can also be fascinating, good, endearing, noble, dignified, fun, sexy, meaningful, desirable, complex, soothing, reassuring, surprising: indeed all the things we only ever knew how to look for in the extra-ordinary. 5. Tragedy The ideology of meritocracy tells us that our outward status can be taken as an accurate reflection of our entire value as human beings. It is a philosophy that trusts in the possibility of moral justice in the here and now, in the status hierarchy: the good will be properly rewarded in this world, the bad will be reliably accorded what they always deep down deserved. The concept of meritocracy renders failure not only materially hard, as it has always been, it makes it psychologically catastrophic in its levels of moral judgement. It denies us any possibility of metaphysical consolation; it leaves no room for any idea of ‘bad luck.’ There can be no one to blame but ourselves – and, therefore, at points, no alternative but to loathe and perhaps do away with ourselves. Yet we should note that not all societies and eras have seen success and failure in such a stark and forbidding terms. In Ancient Greece, another rather remarkable possibility – almost entirely ignored by our own era – was envisaged: you could be good and yet fail. To keep this idea at the front of the collective imagination, the Ancient Greeks developed a particular art form: tragic drama. They put on huge festivals, which all the citizens were expected to attend, to act out stories of appalling, often grisly, failure. There was always a crucial premise built into these stories from the start: the person upon whom failure so dramatically descended was shown to be a really rather good person. In a tragedy, decent, well intentioned, capable souls were shown making minor-seeming errors; they might break an obscure law without meaning to; they might misunderstand something someone said to them; they might draw the wrong conclusion from ambiguous evidence – or they might have a moderate (and common) ‘flaw’ in their character: being a bit irascible, a touch arrogant or perhaps a little impatient. And from this would flow disaster, calumny and the ultimate punishment. It would be the work of the playwright to show in detail how, from almost innocent, minor failings, catastrophe could advance by a series of plausible small steps. The ancient Greeks were offering themselves regular lessons that run directly counter to an ideology of meritocracy. They were emphasising that if someone’s life turns out badly, it is not a sure sign of an undeserving character. What happens to people – and to us – is, to a large extent, in the hands of what the Greeks called ‘fate’ or ‘the Gods’, their poetic manner of saying that things often work out in random ways, according to dynamics that simply don’t reflect the merits of the individuals concerned. Any society, such as ours, which is heavily invested in competition needs to supplement the idea of meritocracy with a realistic and sympathetic notion of tragedy. When we have failed, or when we see others who have, we are frequently encountering the cruel workings of fate and chance. The person (who may also be us) who ends up defeated, alone, in trouble or impoverished may be – if only we could see the whole story properly – sensitive, serious, decent and very unlucky. And their unhappiness may properly deserve the compassion and kindness of all onlookers. A strong, developed sense of tragedy is the necessary counterweight to competition. But our society currently lacks a powerful, wide reaching and reliable institution for promoting a tragic – and hence compassionate – perspective on life. The Greeks had their public theatres, in the past Christianity built its churches around the story of a good man who in worldly terms got nowhere and met a degrading, agonising end. By contrast, today we inhabit a culture that is more interested in humiliating those whose lives have already gone badly wrong than in teaching us the art of tragedy. The natural appetite to condemn is stoked and feels correct – right up to the moment where misfortune strikes us and we are left alone with our sorrows in a hostile, mocking world. 6. Transcendence Secular societies do not orient themselves around devotion to something bigger than, or beyond, themselves. They are not interested in what we can term transcendence: contact with eternal and grand phenomena in comparison with which our ordinary preoccupations can come to feel unimportant and redemptively insignificant in our own eyes. With the receding of religion there is in general nothing left to awe or relativise us. Our immediate difficulties and burdens, our conflicts and pains are, it seems, all there is – and so they loom ever larger and more desperately in our agitated minds. However, the sources of transcendence needn’t be – as religions presumed – composed only of deities. They might involve the sight of the stars at night, spread out like diamonds on a mantle of velvety darkness: uncountably many fiery suns, implausibly distant and themselves constituting only an infinitesimal fraction of the cosmos. We can begin to conceive how vanishingly minor our sun, our planet and we ourselves are in this sublime vastness. Imagined from sufficiently far away, all human differences fade. Our collective similarities seem more evident. Our conflicts and competitions feel less urgent or earnest. Or it might be immersion in a desert that generates our sense of awe. Here, for hundreds of years very little has happened. History has been measured in inches of wind-erosion; a boulder slipped from a hillside three hundred years ago. We’re introduced to an epochal sense of time: it doesn’t matter what we did yesterday or what we may do tomorrow. The normal scale of relevance we apply in our lives is suspended. The crags don’t care who we are; they’re not impressed, or disappointed, by our careers; they don’t ask about our sex lives or our romantic histories. We are returned to a universal common denominator. We might meet a hint of transcendence on a more domestic scale in a small animal: a duck or a hedgehog. Its life goes on utterly oblivious to ours. It is entirely devoted to its own purposes. The habits of its species have not changed for centuries. We may be looking intently at it but it feels not the slightest curiosity about who we are; from its point of view, we are absorbed into the immense blankness of unknowable, incomprehensible things. A duck will take a piece of bread as gladly from a criminal as from a high-court judge; from a billionaire as from a bankrupt felon; our individuality is suspended – and it is an enormous relief. Nature habitually envelops us in forces and sequences that are entirely above and beyond our control. The trees flower in spring and lose their leaves in autumn; the sea rises and falls, the earth spins around the sun bringing winter and summer with no regard at all to us. And, therefore, our individual errors and our failings come to seem irrelevant: the processes of nature will continue with us or without us, whether we mess up or triumph, whether we have been mean or said something asinine. Nature does not upraid us for being fools. A central task of culture should be to remind us that the laws of nature apply to us as well as to trees, clouds and cliff faces. Our goal is to get clearer about where our own tantalisingly powerful yet always limited agency stops – and where we will be left with no option but to bow to forces infinitely greater than our own. Today, the transcendent is real, but disorganised and fragmented. Religions organised it: they interpreted it; they ensured our regular contact with it: they took it to the centre of shared public culture; they insisted on its importance. There continue to be opportunities to meet the transcendent but for the moment they seem to be left to individual chance. The power to bring a consoling perceptive to our troubles is not harnessed by any powerful institution that has our best interests in view. The consolation is there, but we live unconsoled, waiting for the transcendent to be mastered and applied to our inner squalls and sorrows. 7. Good Enough High ambitions are noble and important but there can also come a point when they become the sources of terrible trouble and unnecessary panic, creating a standard of judgment against which our actual lives are bound to fail. Our Romanticism – which sounds so impressive when expressed in art or song – can ruin our chances of maintaining decent, realistic relationships in the world we actually live in. An important corrective to this attitude was developed by the mid-20th century British psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. In his clinical practice, Winnicott often encountered parents who were deeply worried that they weren’t doing a good job of bringing up their children. What struck Winnicott was that, almost always, these were actually perfectly good and loving people. They weren’t perfect, of course. They might be rather busy or a bit short tempered at times or anxiously juggling divergent commitments. But, in all sorts of basic ways, they were what he came to term ‘good enough.’ The notion of ‘good enough’ can be usefully extended across many facets of life and, in particular, relationships. A marriage may be ‘good enough’ even while it has its dark moments. Perhaps at times there’s little sex and a lot of arguments; there are areas of loneliness and non-communication. Yet, at the same time, there are zones of tenderness, kindness and understanding. Instead of being tormented by the imperfections of love, under the aegis of a good-enough philosophy, we can worry less. Actual relationships are never ideal, but they can often offer us enough to get on with our lives. Couples who compromise are not the enemies of love: they may be at the vanguard of understanding what lasting relationships truly demand. They deserve admiration, not condemnation. At its heart, compromise is a recognition that the ideal is not actually on offer; we’re not stupidly or timidly backing down when we might have attained perfection with an extra push. By compromising, we’re honouring how much of the good is actually attainable, given the constraints of a reality we are newly devoted to respecting. 8. Recurrence Modernity is preoccupied by novelty, to our cost, for much that we are and love is not new. The compensation – and consolation – we need lies in carefully reminding ourselves of the balancing importance of things that are recurring and cyclical. When we focus on recurrent history, rather than the news of today, we stand to discover that crises and emergencies, disasters, corruption and incompetence are standard features – to some degree – of all societies. Of course we want things to go better: but if we focus on recurrence we have a wiser sense of what improvements plausibly look like. We won’t be drawn to dramatic solutions, we’ll be more patient with small-scale, boring-sounding incremental steps; we’ll not be too dismayed by inevitable setbacks. If we look at enough relationships through the lens of recurrence, we will similarly start to realise that there are issues that standardly arise and, therefore, are likely to feature in our own loves as well. If we look at enough careers in detail, here too we will discover just how much difficulty and pain lie behind all achievements. That problems occur is not the fault of anyone in particular. They are tied to quite basic features of the human condition: our limited self-knowledge; the fact that we must take decisions from a position of ignorance via our faulty minds. We may temporarily stave off or sidestep problems – but they will always make a return to our lives in some form. They belong to the cyclical downturns of the human condition. Nature is perhaps the supreme teacher of the idea of recurrence. By studying it, we are continually meeting the same patterns: a tree puts out its first buds, it blossoms and comes into leaf; its fruit ripens and falls; the leaves change colour, wither and are blown away by the wind, leaving the branches bare. Our lives are at points no less circumscribed and subject to necessity. Concentrating on the recurrent patterns of nature primes us to understand the structure of our own embodied lives. We should not expect to have mysteriously escaped the laws of existence. We remain part of the cycle of time. There is, thankfully, little that is ever entirely new. The above delineation of eight problems and eight consoling ideas can be condensed in the following table: This article appeared at TheBookOfLife.org | 10.JUL.2018 |

|