PSYCHOLOGY

One of the characteristic possessions of all European nobles for many centuries was an elaborate depiction of their family tree, showing their lineage down the generations.

The idea was that the person sitting at the bottom would see themselves as the product of – and heir to – all that had come before them. The tree gave a quick visual guide to who they were and what others should know about them. If two aristocrats were contemplating marriage, the first thing they would do would be to carefully examine each other’s trees. It can seem like a quaint preoccupation, wholly tied to another age and solely of interest to members of a few grand and ancient families. But the idea of such a tree sits upon a universal and still highly relevant concern: irrespective of the financial and status details of our families, we all have another significant legacy to grapple with: each of us is the recipient of an emotional inheritance, largely unknown to us, yet enormously influential in determining our day-to-day behaviour – normally in rather negative or complex directions. The task of emotional maturity is to learn to understand the details of our emotional inheritance a little before we have been able to ruin our own and others’ lives by acting upon its often antiquated and troublesome dynamics. Some of what we inherit psychologically from our families can of course be extremely positive. Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher and Emperor of Rome in the second century AD, began his Meditations with a touching list of the many positive things he had learned from his relatives: From my grandfather Verus I learned good morals and the government of my temper. From my father, modesty and a manly character. From my mother, piety and beneficence, and abstinence, not only from evil deeds, but even from evil thoughts; and further, simplicity in my way of living, far removed from the habits of the rich. But few of us are quite as lucky as this. Alongside positives, we tend to inherit a great many predispositions which make it harder than necessary for us to cope adequately with adult life, especially in the area of relationships and of work. Were we to repeat Marcus Aurelius’s exercise, it might run in a far darker direction: from my mother, I learnt to lose my temper quickly and give up on being heard properly by people close to me. From my father, I learnt to judge myself by my external achievements only and therefore to feel intense jealousy and panic in the face of professional setbacks. It can be hard for us to know exactly when our emotional inheritance is active in our behaviour, but it is normally signalled by responses which are – in certain ways – excessive, out of place, unwarranted by the facts in the here and now or just highly unsuitable to our own interests and those of people around us. We might, under the sway of aspects of our emotional inheritance, be unable to prevent ourselves from falling in love with violent or neglectful types or we might sabotage our careers whenever they came close to seeming overly impressive or fulfilling. Our emotional inheritance might endow us with a habit of sulking deeply whenever we are slightly misunderstood or of being rigidly cheerful and unwilling to look at the downsides when we are planning our futures. A lot in our inheritance works against our chances of fulfilment and well-being because its logic doesn’t derive from the present; it involves a repetition of behaviour that was formed and learnt in childhood, typically as the best defence we could cobble together in the face of a difficult situation. Unfortunately, it is as if part our minds hasn’t realised the change in our external circumstances, it insists on re-enacting the original defensive manoeuvre even in contexts that don’t warrant or reward it. It might once have made sense to try to see the good side and attract the loyalty of a parent though they were neglectful and sometimes violent: there were few other options when one was three. But to continue to associate affection with violence and neglect is to impose intolerably narrow restrictions on one’s adult love choices. Our emotional inheritance clings to us because it was bequeathed in conditions of total helplessness. The early years were periods of acute vulnerability. We were utterly at the mercy of the prevailing environment. We could not properly move, speak, control or contain ourselves; we could not calm ourselves down or recover our equilibrium. We had no choice about whom to direct our feelings towards and no way to defend ourselves adequately against what injured us. We could not even string thoughts together, needing the language eventually lent to us by others in order to begin to interpret our requirements. Even in the most benign of circumstances, with only the best intentions at play, the possibilities for warps and distortions were hence enormous. Few of us ever come through entirely unscathed. What we experienced in those early years now moulds the expectations with which we approach the people and situations of our adult lives. What we feel we’re owed, how we speak to ourselves, our sense of how our hopes may turn out, all are extrapolations from experiences and relationships of a distant past whose particulars we may find it hard to recall. A lot of our difficulties stem from these unknown psychological legacies, which interfere with our ability to respond with appropriate lucidity, courage, affection, directness or soberness to the present. We interpret reality with a bias which twists the available evidence according to a narrative that feels familiar – but may be untrue to what and who is actually before us. When our powers of comprehension and control were not yet properly developed, we may have become preternaturally nervous, suspicious, hostile, sad, closed, furious or touchy – and are now at risk of becoming so once again whenever life puts us in an environment that is even distantly evocative of our earlier troubles. But so bad are we at recognising our inherited misreadings that we cannot prevent ourselves from re-engaging our ancient defences, let alone inform others of them in a way that would win us sympathy and forgiveness. Painfully for those who care for us, we may have no easy way of knowing, let alone calmly explaining, what we are up to; we simply feel that our response is entirely appropriate to the occasion. We lose sympathy because we can’t lay bare in good time, with appropriate evocation, the reasons why we are behaving as we are. We just seem a bit mad, mean or annoying. Psychotherapists have developed a special term to capture what we inherit emotionally from the past: they call it our ‘transference’. In their view, each of us is constantly at risk of ‘transferring’ patterns of behaviour and feeling from the past to a present that doesn’t realistically call for it. We feel a need to punish people who aren’t to blame; we worry about a humiliation which isn’t anywhere on the cards; we’re compelled to betray as we were once, three decades before, betrayed . Ideally, we’d build up a storehouse of knowledge of what exactly we had inherited (and from whom), a kind of emotional family tree that would show us – and others – the issues that had been transferred across generations and were liable to be disrupting our lives today. Psychotherapists have made it one of their central task to help us tease out our emotional transferences before they cause us too much damage. A lot of therapy involves trying to trace the history of certain of our present-day attitudes and behaviours. In a sympathetic setting, we may be moved to sense and conquer some of our eccentricities and knee-jerk responses: we might come sympathetically to discuss just why we tend to go cold when someone offers us warmth or why and how it has come to be that we sometimes descend into destructive rages when we feel belittled in professional contexts. Because a classic way of denying that emotional transference is involved is to insist that the present situation warrants our response, psychologists have developed certain tests that are deliberately rather ambiguous in their nature – and hence more likely to throw up evidence of inherited background feelings which we impose upon our current circumstances. The most well-known of such tests was devised in the 1930s by the Swiss psychologist Hermann Rorschach, who created a group of ambiguous images, then asked his patients to reflect without inhibition on what they felt these looked like, evoked and made them think of. Hermann Rorschach, Inkblot test, 1932

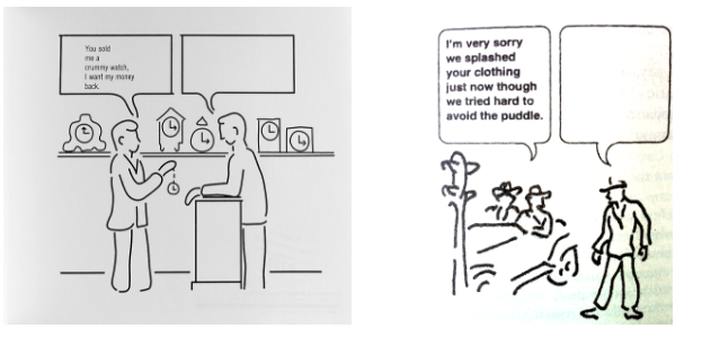

Crucially, these images have no predetermined meaning; they aren’t about anything in particular. They are suggestive in a huge variety of directions – and so different people will see different traits and atmospheres in them according to what their past most readily predisposes them to imagine. To one individual who has inherited from their parents a rather kindly and forgiving conscience, an image could be seen as a sweet mask, with eyes, floppy ears, a covering for the mouth and wide flaps extending from the cheeks. Another, more traumatised by a domineering father, might see it as a powerful figure viewed from below, with splayed feet, thick legs, heavy shoulders and the head bent forward as if poised for attack. With similar intent, the psychologists Henry Murray and Christiana Morgan created a set of drawings showing people whose moods and actions were deliberately indeterminate. In one example, two men are positioned close to one another with their faces able to bear a host of interpretations. ‘It’s perhaps a father and son, mourning together for a shared loss’, one respondent who had inherited a close relationship with his father might say. Or another, bearing the burden of a punitive past, might assert: ‘It’s a manager in the process of sacking a young employee who has failed at an important task’. Or a third, wrestling with a legacy of censured homosexuality, might venture: ‘I feel something obscene is going on out of the frame: it’s in a public urinal, the older man is looking at the younger guy’s penis and making him feel very embarrassed but perhaps also somehow turned on….’ One thing we do really know is that the picture doesn’t show any of these things, the elaboration is coming from the person who looks at it, and the way they elaborate, the kind of story they tell, is saying far more about their emotional inheritance than it does about the image. Henry Murray, Christiana Morgan, Thematic Apperception Test, 1935 Following this pattern, in the 1950s, the American psychologist Saul Rosenzweig designed tests to tease out our inherited ways of dealing with humiliation and bad news. His Picture Frustration Study (1955) showed a range of situations to which our psychological histories would give us very different templates of responses. Saul Rosenzweig, Rosenzweig Picture Frustration Study

One kind of person, the bearer of a solid emotional inheritance, will tend to be resilient when someone has behaved badly towards them or is causing a problem unnecessarily. They aren’t happy about their frustrations, but their main aim is to repair the damage and they can do so without feeling shaken to their core. They don’t need to take bitter revenge or get the other person to feel guilty or stay quiet. They know there is such a thing as an accident and a difference between intention and effect. They think it’s normal to treat people well – they do – and if someone else falls below their standards, they’re not embarrassed to tell them so in plain terms. It won’t be a catastrophe, just a few unpleasant moments and then the relationship can improve over the long-term. All of which can feel entirely alien when we have inherited a backdrop of shame around the expression of our true desires. Somewhere in our past we may have embraced the idea that we deserve quite bad treatment from others: it’s very unpleasant but it feels strangely appropriate. We may have learned in childhood to carry with us a reservoir of free floating inadequacy, we’ve become so conscious of our own shortcomings that we’re never very surprised when insult occurs. A fourth transference exercise asks us to say the very first thing that comes to mind when we try to finish particular sentences that are fired at us. For example: The idea is to prevent our wily conscious minds, which know a little too much about how to seem normal, from censoring emotional eccentricities which we would be wiser to bring into the open and learn from. Being asked not to think too much when we answer allows the attitudes that actually guide us to emerge and perhaps reveal – usefully for us – how much they don’t in fact suit who we would like to be in the present. A sign of maturity is to accept with good grace that we might be involved in multiple transferences, and to commit oneself to rationally disentangling these, so that we will not need to keep making things tougher for ourselves and everyone around us. The task of growing up is to realise with due humility the exaggerated dynamics we may constantly be bringing to situations and to monitor ourselves more accurately and more critically so as to improve our capacity to judge and act in the here and now with greater fairness and neutrality. Unfortunately, to admit that we may be drawing on the confusions of the past to force an interpretation onto what’s happening now seems humbling and not a little humiliating: surely we know the difference between our partner and a disappointing parent, between a husband’s short delay and a father’s permanent abandonment; between an argument at the office and a sibling rivalry in the nursery? The business of repatriating emotions emerges as one of the most delicate and necessary tasks of maturity. In this context, the project of drawing up an emotional family tree is intended to provide a record of key bits of our emotional inheritance – identifying the people and situations in our past that have given rise to habits of mind that lead us to see current events in particular ways. The idea is to grow a little wiser as to where our troubles are coming from and around what areas of our lives we will therefore need to be especially careful. Traditionally, family trees didn’t just exist to tell people about themselves. They were public objects intended to convey to strangers what they needed to know about us. Before grand people got married, they would carefully scan each other’s trees to know what was at stake. An emotional family tree would have a similar value in letting others know more about us in contexts when they might still be sympathetic – before we’ve had a chance to damage or enrage them with our inheritance. Knowing the risks of transference prioritizes sympathy and understanding over irritation and judgement. We can come to see that sudden bursts of anxiety or hostility in others may not always be directly caused by us – and so should not always be met with fury or wounded pride. Bristling and condemnation can give way to compassion for the difficulties all of us have with our pasts. In a perfect world, two people on an early dinner date would be expected to swap beautifully drawn family trees called, perhaps, ‘My Emotional Inheritance’. Such a tree would also be something to give at a wedding and would be required at work, as a supplement to a CV. Having a complex emotional inheritance wouldn’t be a source of shame, the pride would be that one understood its constituent parts. We don’t need people to be perfect; we simply need them to be able to explain the greater part of their inherited imperfections calmly and in good time, before we are enmeshed in the sufferings they can otherwise cause us. |

Vertical Divider

|

5things

weekly bulletinA weekly bulletin of the 5 most recommended articles, challenging ideas and interesting new things in Psychology from

NIKOS MARINOS CONSULTANCY delivered straight to your inbox, every Monday. |