⊕ PSYCHOLOGY

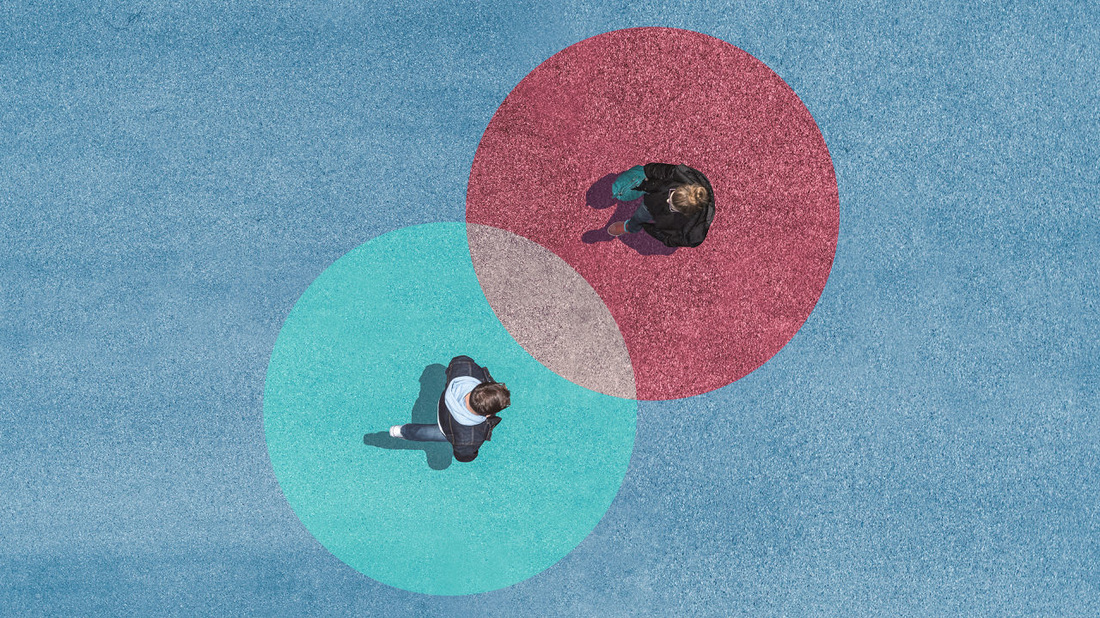

It’s hard for us to be anything other than deeply self-centred. Our own irritations, regrets, desires and ambitions have an unparalleled hold on us and loom larger than pretty much anything else in our minds, including the suffering of an unknown child, an earthquake near Valparaíso or an asteroid-strike on the side of planet Kepler 186f, 490 light years away. We have no option but to cleave very tightly to our own agenda.

Yet we also possess, albeit frequently in undeveloped forms, a talent for Detachment, a capacity for loosening our consciousness from its normal moorings in order to contemplate existence for a time without us as its central character. Though we are always anchored to our own wheezing vulnerable bodies, our minds possess, at least in part, a more immaterial and vagabond character that can wander more promiscuously and disinterestedly amongst ages, peoples and places. There are moments – they might come late at night or in the quiet chill of dawn – when we are freed from the customary burdens of being ‘ourselves’, which means, from having to take our own sides and battling for our own interests – and can survey existence from a greater height, without the weight of our innate egoism. We can fly with greater dispassion over events, seeing with less self-distortion the reality of the lives of others, picturing to ourselves what it might be like to be someone else, something else (perhaps a rock or leaf) – or not to be at all. Things may happen to us without we – for that matter – needing to stay loyal to their every resonance. We have a measure of choice how much we stay involved with the ego. Our normal anxieties and obsessions can relax their grip on us: what happens to us no longer needs to feel so critical. We are able to float on wider currents, surrendering with a certain blitheness to the ways of the universe. In early 16th century in Europe, a new type of portrait arose, which typically showed a preoccupied individual, seated with their back to an open window – through which we (the viewers) could see a magnificent, extensive natural landscape. One example is the Portrait of a Man with Glasses by Quentin Massys, painted in Antwerp around 1520. Quentin Massys, Portrait of a Man with Glasses He might be a banker or a sugar trader. Antwerp was the centre for this global trade at the time and the greatest commercial city on earth. Or perhaps he is a scholar engrossed in the minute analysis of a complex grammatical point in one of the ancient classical texts that were much admired at the time. His glasses – which would have been highly expensive – are the outward symbols of a certain myopia, a strained devotion to what is near. But outside, if only the man were capable of Detachment, he would see mountains, a castle, a great river running to the sea, distant valleys and a delicate blue sky shading to white at the horizon – symbols of vast worlds and great possibilities. The man is not ridiculous. In a touching way, he is only exactly like us: preoccupied, busy, and with his back to the bigger view behind him. Moods when we can detach and turn to this bigger view may seem as if they visit us wholly at random, but once their intellectual structure is understood, they can to a degree be choreographed and fostered, and so drawn upon to assist us at moments of agitation and restlessness. The core move is to learn to reframe our lives within the far larger context of what we can broadly call Nature, that boundless eternal dynamic multi-planetary setting in which every individual life unfolds and within which we are all reduced to sub-atomic insignificance. Nature offers us a range of ways to reframe our experiences and thereby gain a measure of serenity and relief from the most aggravating of our immediate circumstances: I: Other Realms We have probably been living in the same city for a while. The twenty people we have to deal with every day at work overwhelm our field of vision – as are our families, with all their challenges and compromises. We know our environments pretty well. The result can be a deadening or ennervating claustrophobia. Which is why it may come as such a relief to be confronted by examples of the ongoing existence of alternative natural realms and habitats, every bit as complex, admirable and dramatic as our own. Part of what makes Albrecht Durer’s The Large Piece of Turf, completed in 1503, moving is that we have of course so often looked at what he depicts and noticed so little. We probably registered only generic categories like ‘grass’ or ‘a bit of wasteland’. But he spotted a whole universe lying unseen beneath our feet, each blade endowed with its own distinctive character and destiny. The drawing is not, in the end, about grass at all – so much as it is about a gentle invitation to forego egoism. There are similar lessons on hand in John Ruskin’s meticulous observation of the feathers of birds, humble structures which it normally never occurs to us to include in our sense of what matters – and yet which Ruskin knew how to love (offering us, thereby, in passing, a definition of what love might be: a power to give oneself over to something that is not-I). John Ruskin, Peacock FeatherIn a comparable step, in the early 1820s, John Constable devoted himself to studying the skies around him in Hampstead, producing some 600 studies of clouds in different moods in a quest to help us note the otherwise invisible, awe-inspiring soundless drama above us. John Constable, Spring Clouds Study (1822 )After immersion in these alternative worlds, our own life and obsessions can start to feel markedly less precious and central. We may imaginatively fuse with natural things, becoming for a time not just ourselves – with our particular histories and compulsions – but also the dandelion, the wind, the cloud or the wave breaking on the shore. From this point of view, status is nothing, possessions don’t matter, grievances lose their urgency. If certain people could encounter us at this point, they might be stunned by our reserves of generosity and sympathy. Virginia Woolf was frequently beset by struggles: insecurity about her position in the literary world, unhappiness with members of her family, jealousy of rivals. But she also knew how to detach herself and, on occasion, to look very closely at moths. In what is perhaps the finest piece of prose she ever wrote, The Death of the Moth, published in 1942, Woolf records her thoughts as she sits in her study watching an ordinary moth struggling to find a way out from behind a pane of glass whose structure it can’t understand. Rarely have such tender, empathetic thoughts been eked out from such an apparently unpromising situation – though it was Woolf’s genius to know that there are, in fact, no such things as minor situations: “One could not help watching him. One was, indeed, conscious of a queer feeling of pity for him. The possibilities of pleasure seemed that morning so enormous and so various that to have only a moth’s part in life, and a day moth’s at that, appeared a hard fate, and his zest in enjoying his meagre opportunities to the full, pathetic. He flew vigorously to one corner of his compartment, and, after waiting there a second, flew across to the other. What remained for him but to fly to a third corner and then to a fourth? That was all he could do, in spite of the width of the sky, the far-off smoke of houses, and the romantic voice, now and then, of a steamer out at sea.” It could seem as if Woolf was doing the moth a favour; rescuing it from its ignored existence. But, in truth, the benefit ran as much in the other direction: the moth was helping Woolf – and we by extension – with some of the myopia and attendant sense of suffocation that stems from having to be always ourselves amd concerned with our own sort. II: Animal Indifference Some of the relief of the animal world stems from its magisterial indifference to all that we are. It has never occurred to a cow to wonder what your prospects might be. Frogs are admirably indifferent to your address book. The things that have been tormenting you, the hopes and sorrows that circulate through your messy life, are pleasantly meaningless to the duck confidently marching her young down to the river. A career is of no import to the hedgehog. He isn’t frustrated because it has never occurred to him to want to be understood. He hasn’t heard of love, status or money. Fish are no less educative. One is struck by the beauty and strangeness of what nature has produced beneath the ocean: the oyster that somehow generates its own home, rocky on the outside, suggestively smooth and polished within, the sole, one of whose eyes has to migrate rounds it head on the path to maturity and the monkfish whose huge, toothy mouth and puny body are so offensive to our sense of beauty and yet so useful to its survival. In a universe composed almost entirely of gas and rock circulating in the endless nothingness of space – we are their cousins, with whom we briefly cohabit the surface zones of Earth. In the recent history of the cosmos, we shared common ancestors, whose progeny became diversely the octopus, the sea bream or evolved gradually into solicitors, psychotherapists and graphic designers. We can imagine spending this thing called life embodied in a lobster, encountering the world through its tiny peppercorn eyes, which offer a field of vision so much wider but less focused than our own. Like so many creatures, those of the sea are agents of re-enchantment. We suffer fateful tendencies to absorption in our disappointments and particularities. Then, looking into the eye of a mullet, or contemplating the internal architecture of a skate fin, one is reconnected with a primordial complicated Otherness that – thankfully – cares nothing for us. Our fellow creatures help us to see that we may have been judging everything far too narrowly and from too slanted a perspective. The judgement and follies of all those humans we worry about so much really does not have to be the end of us. III: Moral Blindness Much about our lives can seem unfair. Others have more than us. Certain things we were promised never came through. We’ve been the victim of extreme nastiness and callousness. Again, Nature detaches us from our wounded ego-centric perspective. The cheetah is not responsible for its nature, it isn’t being ‘nasty’, it didn’t choose to live by stalking antelope and ripping the flesh from the still steaming, blood filled haunches of the wildebeeste. It does not ask to be excused or pitied; it has no will to explain itself. It is neither proud nor humble. It has no ego. It does not tell itself a special story about its own life. It does not worry about tomorrow or rue what happened yesterday. In 1810, the English artist Turner witnessed an avalanche devastating a valley in the Grisons region of Eastern Switzerland. Twelve people died. A hamlet was flattened, herds of cows were swept to oblivion, trees that had stood for hundreds of years were ripped from their moorings in an instant as if they were twigs. J. M. W. Turner, The Fall of an Avalanche in the Grisons (1810) But this was not revenge or punishment. Nature cannot think about individuals. The atoms that make up every living thing are only temporarily assembled into a specific form, before they are pulled apart again by entropic forces and reassembled as something else. To nature it doesn’t matter whether they are embodied in a cockroach, a turkey or a senior magistrate looking forward to a break in Venice which will be interrupted by a heart attack. A mountain doesn’t care how long it took to build the little bridge over the brook. It is fine (nature holds) that a salmon should lay three thousand eggs and that only two should complete the life cycle. The shoal, the herd, the species, count far more than any particular member. The giant forest fire will end thousands of small lives (voles, marmosets and otters) but thousands more will take their place; ancient trees will die but hundreds of saplings will within months sprout their tender fingers in the newly opened spaces. Nature isn’t opposed to us per se, it just follows laws which will inevitably leave most of our hopes crushed – yet without evil intent. It’s simply a law that children are almost always ungrateful to their parents, that true love is close to impossible, that everything that lives must die, that the mountain will be destroyed by the earthquake, that the lamb will be carried off by the eagle, that the rat will bite the rabbit, that we will be overlooked for promotion, that the penguin will die in the blizzard, that cancer will gnaw our bowels, that the gently nurtured egg will be shaken from the tree in a spring squall and shatter on a rocky ledge beneath. In the mid-sixteenth century, the Netherlandish artist Pieter Bruegel painted a picture illustrating the ancient classical story of Icarus. Icarus had been too eager to defy nature and despite his father’s urgent warnings, flew too close to the sun – melting the wax of his flying machine. He fell headlong into the sea and was drowned. It’s a dramatic story, and yet when Bruegel painted it, he made an odd but important decision. He nearly left Icarus out of the image. All we can see his his leg disappearing into the water just off the rock behind the stern of the ship. In the meantime, everything goes on as normal. Bruegel took particular care in depicting the beautiful mountains, some delicate trees, a flock of pensive sheep, the spray upon the surface of the sea. The situation was perfectly summarised by the English poet, W. H. Auden, in a poem published in 1939: In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry, But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on. – W. H. Auden, Musée des Beaux Arts Auden’s words can seem, at first sight, simply like a criticism of an unresponsive universe. Shouldn’t the onlookers get more agitated and excited? Why don’t they realise something appalling yet tremendous has just occurred? Why doesn’t the world stop in the face of disaster? But there’s another way we might read the situation. They – the people, animals and rocks who keep going about their business – represent a wider view, which nature encourages. Our Icarus-like calamities are strangely far less important in the bigger picture than we suppose. We’ll mess up, we’ll plunge out of the sky, we’ll spoil an opportunity or make a stupid blunder; we’ll die. But the world will go on. Few people will care. They’ll mostly (as the big view, reveals) get on with doing whatever they were doing before. Our fall and splash won’t matter very much. From our perspective, what happens to us is decisive. From Nature’s standpoint, it’s no more notable than the death of an earthworm – which is at once a little sad and also, more surprisingly, hugely reassuring. For our peace of mind, we need regularly to tap into a perspective in which we ourselves are not the leading figures and in which how our own lives go is not the decisive issue. By expanding our mental horizons, seeing life and the world without seeing ourselves as individuals at the centre of it, we diminish our significance – along with our insistent anxieties and ego-wounds, thereby opening up new opportunities to forgive and be kind to our temporary, fragile identities. IV: Submission It is normal to respond with enormous anger to frustrations of our wills. We shout because they, the cruel others, cannot see our point, did not let us have our way. We are driven by an innate desire to see our wishes enacted upon the world. But despite our screams, frustration is a constant. People will always find objections to our plans. Our calls will not be returned. Less intelligent or accomplished rivals will get ahead. We will be exhausted by humanity’s collective resistance. Then, perhaps heading back to the airport after another series of maddening meetings, we might catch sight of the sunset behind the mountains. Tiers of clouds are bathed in gold and purple, huge slanting beams of light cut across the city. It seems as if one’s attention is being drawn up into the radiant gap between the clouds and the hills, and that one is for a moment merging with the cosmos. It now doesn’t seem to matter so much what happened at the office or the fact that the contract will – maddeningly – have to be renegotiated by the Paris team. It’s simply deeply calming to be absorbed in the contemplation of something so manifestly bigger than oneself. One doesn’t even mind particularly when the flight is delayed by an hour. Overwhelmed by nature’s grandeur, we are offered a vivid, consoling sense of our relative littleness. Nature sends us a humbling message: the incidents of our lives are not terribly important in the scheme of things. And yet rather than being distressing, this sensation counteracts the debilitating sense that everything matters so much, that they might be different and that we have not achieved the significance we expected of ourselves. In the world’s deserts, in forests, on the sides of glaciers, in front of the oceans, we can meditate on the utter insignificance of all human achievements, measured against the larger sweep of biological and geological time. It might have been two hundred million years ago that the Triassic seas retreated, and the land rose up to form a plateau. The trees might have been known to the dinosaurs. Nature undercuts the gradations of the human time scale and hierarchy, relativising every achievement. Nature is a corrective to our intemperate impatience. It suggests that year by year, little will change; a few more stones will crumble; a few plants will eke out an existence; the same pattern of light and shadow will be endlessly repeated. Caring about having a larger office or being worried that one’s car has a small scratch over the left rear wheel doesn’t make much sense against the enormity of time and space which we behold in the sublime places of nature. The differences in accomplishments, standing and possessions between people are no longer especially exciting or impressive, when considered against the emotional state that a canyon or cliff-face promotes. Nature tells us that there is no urgency. Things happen on the scale of centuries. Today and tomorrow are essentially the same. Your existence is a small temporary thing. You will die and it will be as if you had never been. The clouds and the daisies were here before – when pterodactils roamed – and they won’t notice when we are all gone. The tree over there is disintegrating. Before too long, branches will fall off; the sap will no longer get to the outer twigs; it will be burnt in a lightning strike and then it will be as if it never was. This will happen, in some version or another, to everyone and therefore to us. The course of nature is inevitable. Whatever our lives are to our own imaginations, they are not so terribly important to the cosmic story – with whose remorseless inevitable path we are invited to identify with a degree of grandeur and heroism, becoming great through full acceptance of our puniness. It could all sound demeaning. But these are generous sentiments given the suffering that flow from unwittingly exaggerating our own importance or clinging to false notions of permanence. Nature does not humiliate us by exalting itself – it redeems us by giving us a sense of the lesser status and inherent fragility of all of wretched humanity. There is consolation too to be found in the sky at night. On an evening walk, once you are passed the phone masts and the bright lights of the shopping mall, you can look up and see Venus and Jupiter shining in the darkening sky. When dusk deepens you can see Andromeda, Aries and a billion other stars, hints of the unimaginable extensions of space across the solar system, the galaxy and the cosmos. They were there, quietly revolving, their light streaming down, as spotted hyenas warily eyed a stone age village; and as Julius Caesar’s triremes set out after midnight to cross the channel and see the cliffs of England at dawn. News of the fall of the Roman empire hasn’t arrived yet on GNz11, in the Ursa Major constellation, 32 billion light years from earth – nor details of our quarterly budget review; the state of our marriage or the compromises of our sexual arrangements. Everything that happens to us, or that we do, is of no consequence whatever from the point of view of the universe. The Dutch philosopher Spinoza, a keen astronomer, recommended that regular contemplation of the stars should not be of benefit just to specialists who wanted to know of specific stars: it was to be a route to wisdom for all, simply in its broad strokes. It would, he argued, help us to make a distinction between two ways of looking at our lives, one in which we thought of them egoistically, from our limited point of view, as he put it: Sub specie durationis – under the aspect of time And another in which we could detach ourselves and look at humanity without reference to itself, considering the cosmos: Sub specie aeternitatis – under the aspect of eternity The wise human was, wrote Spinoza, not someone who knew the details of planetary motions, it was someone who had accepted the need to make regular appointments with the eternal gaze. **** States of detachment can only ever be rather short lived – we retain many important practical tasks we need to attend to. But we should take care to be more regular in our encounters with Nature. It isn’t that we must go into Nature at every turn, the idea of it is enough. We need simply summon its most useful elements to our minds at moments of irritation and vengefulness – using it as a tool to cleave ourselves away from the worst dimensions of our egoism. Through Detachment, we may hope gradually to triumph over the primitive mind and find a conduit to an Olympian melancholy serenity. |

MORE

|

|