THEORY | LITERATURE

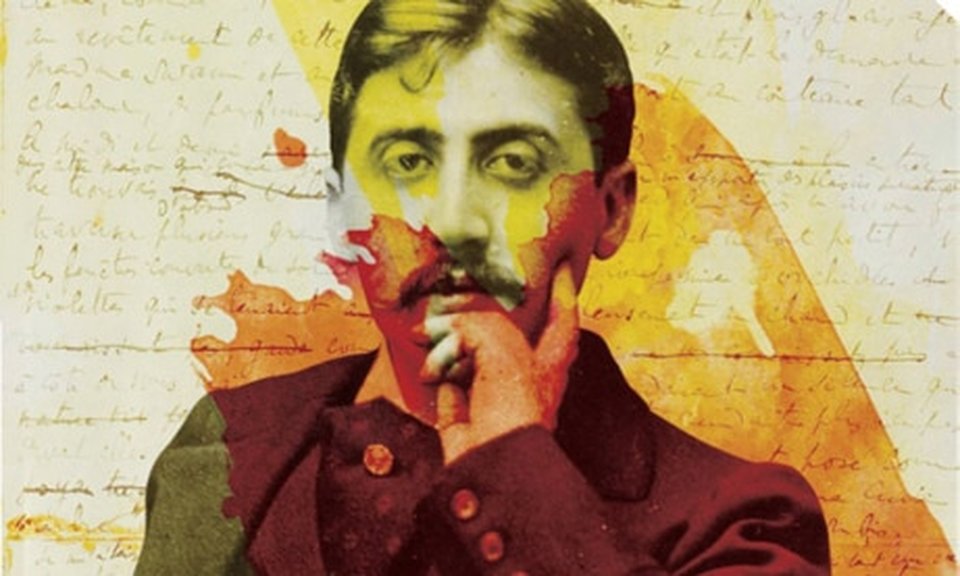

MARCEL PROUST

|

Marcel Proust was an early 20th-century French writer responsible for what is officially the longest novel in the world: À la recherche du temps perdu – which has 1,267,069 words in it; double those in War and Peace.

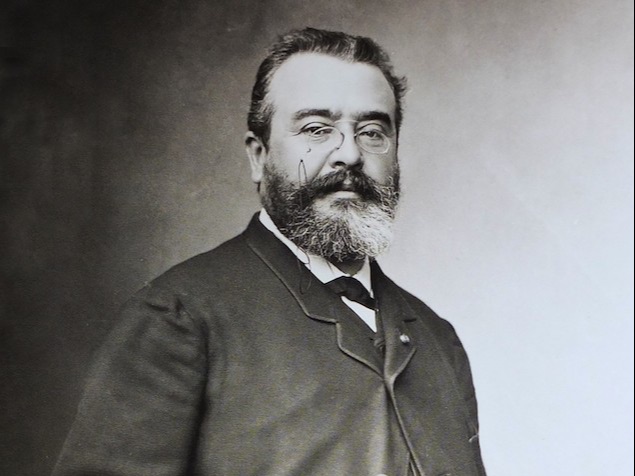

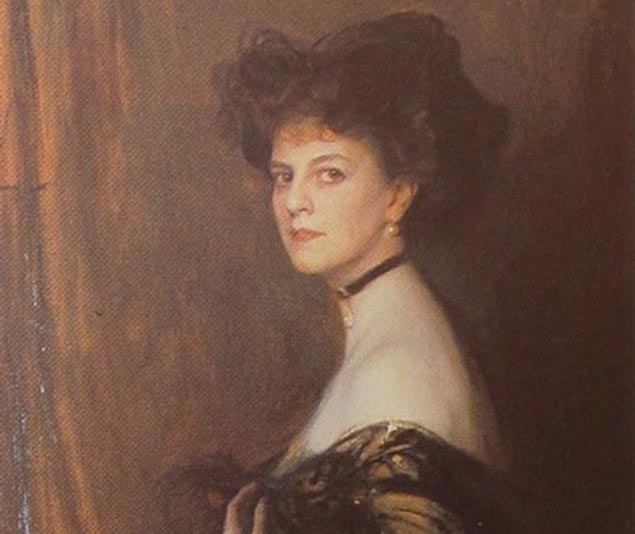

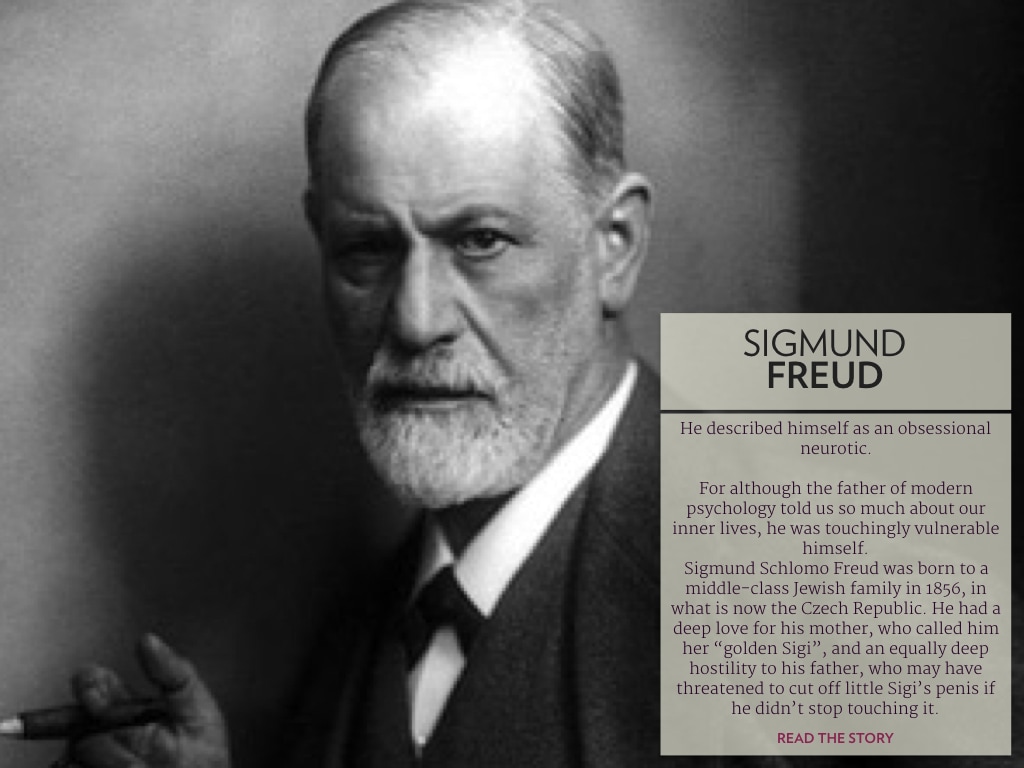

Marcel Proust (seated), with Robert de Flers (left) and Lucien Daudet (right), ca. 1894The book was published in French in seven volumes over 14 years: Du côté de chez Swann, 1913 À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs, 1919 Le Côté de Guermantes, 1920 Sodome et Gomorrhe, 1922 La Prisonnière, 1923 Albertine disparue, 1925 Le Temps retrouvé, 1927 It was immediately recognised to be a masterpiece, ranked by many as the greatest novel of the century, or simply of all time. What makes it so special is that it isn’t just a novel in the straight narrative sense. It is a work that intersperses genius-level descriptions of people and places with a whole philosophy of life. The clue is in the title: À la recherche du temps perdu In Search of Lost Time The book tells the story of one man – a thinly disguised version of Proust himself – in his developing search for the meaning and purpose of life. It recounts his quest to stop wasting time and start to appreciate existence. Marcel Proust wanted his book to help us. His father, Adrien Proust, had been one of the great doctors of his age, responsible for wiping out cholera in France. Towards the end of his life, his frail, indolent son Marcel, who had lived on his inheritance and had disappointed his family by never taking up a regular job, told his housekeeper Celeste: ‘If only I could do for humanity as much good with my books as my father did with his work.’ The important news is that he amply succeeded. Proust’s novel charts the narrator’s systematic exploration of three possible sources of the meaning of life. The first is: SOCIAL SUCCESS. Proust was born into a comfortable bourgeois household; but from his teens, he began to think that the meaning of life might lie in joining high society, which in his day meant, the world of aristocrats, of dukes, duchesses and princes. We shouldn’t think ourselves superior for having no interest in these types. We’re much more likely to be implicated if we convert this category to its present day equivalent: celebrities and business tycoons. For years, the narrator devotes his energies to working his way up the social hierarchy; and because he’s charming and erudite, he eventually becomes friends with lynchpins of Parisian high society, the Duke and Duchesse de Guermantes. Count Henry Greffulhe, 1881, who served as the model for the Duke of GuermantesBut a troubling realisation soon dawns on him. These people are not the extraordinary paragons he imagined they would be. The Duc’s conversation is boring and crass. The Duchesse, though well mannered, is cruel and vain. Marcel tires of them and their circle. He realises that virtues and vices are scattered throughout the population without regard to income or renown. He grows free to devote himself to a wider range of people. Though Proust spends many pages lampooning social snobbery, it’s in a spirit of understanding and underlying sympathy. The urge to social climb is a highly natural error, especially when one is young. It is normal to suspect that there might be a class of superior people somewhere out in the world and that our lives might be dull principally because we don’t have the right contacts. But Proust’s novel offers definitive reassurance: life is not going on elsewhere. The second thing that Proust’s narrator investigates in his quest for the meaning of life is: LOVE. In the second volume of the novel, the narrator goes off to the seaside with his grandmother, to the vogueish resort of Cabourg (the Barbados of the times). There he develops an overwhelming crush on a beautiful teenage girl called Albertine. She has short hair, a boyish smile and a charming, casual way of speaking. For about 300 pages, all the narrator can think about is Albertine. The meaning of life surely must lie in loving her. But with time, here too, there’s disappointment. The moment comes when the narrator is finally allowed to kiss Albertine: “Man, a creature clearly less rudimentary than the sea-urchin or even the whale, nevertheless lacks a certain number of essential organs, and particularly possesses none that will serve for kissing. For this absent organ he substitutes his lips, and perhaps he thereby achieves a result slightly more satisfying than caressing his beloved with a horny tusk…’ The ultimate promise of love, in Proust’s eyes, is that we can stop being alone and properly fuse our life with that of another person who will understand every part of us. But the novel comes to dark conclusions: no one can fully understand anyone. Loneliness is endemic. We’re awkward, lonely pilgrims trying to give each tusk-kisses in the dark. This brings us to the third and only successful candidate for the meaning of life: ART For Proust, the great artists deserve acclaim because they show us the world in a way that is fresh, appreciative, and alive. Now the opposite of art for Proust is something he calls habit. For Proust, much of life is ruined for us by a blanket or shroud of familiarity that descends between us and everything that matters. It dulls our senses and stops us appreciating everything, from the beauty of a sunset to our work and our friends. Children don’t suffer from habit, which is why they get excited by some very key but simple things like puddles, jumping on the bed, sand and fresh bread. But we adults get ineluctably spoilt; which is why we seek ever more powerful stimulants (like fame and love). The trick – in Proust’s eyes – is to recover the powers of appreciation of a child in adulthood, to strip the veil of habit and therefore to start to look upon daily life with a new and more grateful sensitivity. This for Proust is what one group in the population does all the time: artists. Artists are people who strip habit away and return life to its deserved glory, for example, when they lavish appropriate attention upon water lilies or service stations. Proust’s goal isn’t that we should necessarily make art or be someone who hangs out in museums. It’s to get us to look at the world, our world, with some of the same generosity as an artist, which would mean taking pleasure in simple things – like water, the sky or a shaft of light on a roughly plastered wall. It’s no coincidence that Proust’s favourite painter was Vermeer: a painter who knew how to bring out the charm and the value of the everyday. The spirit of Vermeer hangs over his novel: it too is committed to the project of reconciling us to the ordinary circumstances of life – and some of Proust’s most compelling pieces of writing describe the charm of the everyday: like reading on a train, driving at night, smelling blossom in spring time and looking at the changing light of the sun on the sea. Proust is famous for having written about the dainty little cakes the French call ‘madeleines’. The reason has to do with his thesis about art and habit. Early on in the novel, the narrator tells us that he had been feeling depressed and sad for a while when one day he had a cup of herbal tea and a madeleine – and suddenly the taste carried him powerfully back (in the way that flavours sometimes can) to years in his childhood when as a small boy he spent his summers in his aunt’s house in the country. A stream of memories comes back to him, and fills him with hope and gratitude. Thanks to the madeleine, Proust’s narrator has what has since become known as A PROUSTIAN MOMENT: a moment of sudden involuntary and intense remembering, when the past promptly emerges unbidden from a smell, a taste or a texture. Through its rich evocative power, what the Proustian moment teaches us is that life isn’t necessarily dull and without excitement – it’s just one forgets to look at it in the right way: we forget what being alive, fully alive, feels like. The moment with the tea is pivotal in the novel because it demonstrates everything Proust wants to teach us about appreciating life with greater intensity. It helps his narrator to realise that it isn’t his life which has been mediocre, so much as the image of it he possessed in voluntary memory. “The reason why life may be judged to be trivial although at certain moments it seems to us so beautiful is that we form our judgement, ordinarily, not on the evidence of life itself but of those quite different images which preserve nothing of life – and therefore we judge it disparagingly.” That’s why artists are so important. Their works are like long Proustian moments. They remind us that life truly is beautiful, fascinating and complex, and thereby they dispel our boredom and ingratitude. Proust’s philosophy of art is delivered in a book which is itself exemplary of what he’s saying; a work of art that brings the beauty and interest of the world back to life. Reading it, your senses are reawakened, a thousand things you normally forget to notice are brought to your attention, he makes you for a time, as clever and as sensitive as he was – and for this reason alone, we should be sure to read him and the 1.2 million life-giving words he so deftly assembled. |

MORE

|